The commercial production of crude oil from unconventional sources, which began with the entry of the US shale oil has had a tremendous effect on the global oil market. First it highlighted the flaw of the Oil Peak theory that predicted a climax in total word output by 2012, and from then on, a drastic decline due to the principle of depletion.

While this may be true for conventional oil without the consideration of the impact of technology to facilitate enhanced oil recovery, unfortunately it is not the same with non-conventional oil. Production at a large scale have increased world output. This has favorably positioned demand against supply, leading to the drop of oil price in the global market.

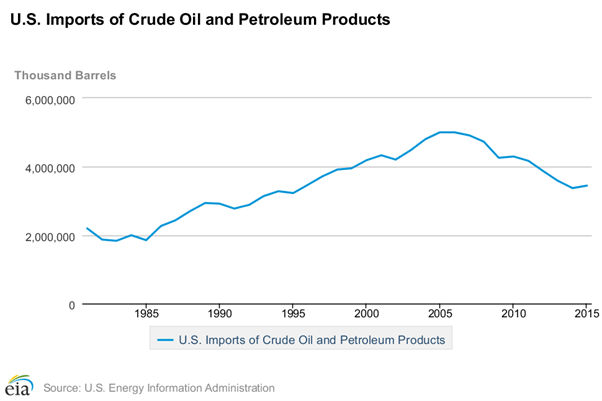

Additionally, it has contributed to the loss of market share of long-time producers of conventional oil and gas. The US had for a great while been the major destination of Nigeria’s Light crude, and its imports peaked at an annual total of 5,003,082 barrels in 2006, slide to 3,878,852 barrels in 2012 before reaching its lowest point of 3,448,734 in 2015 (EIA, 2016).

(The chart below depicts the US oil import from Nigeria, dropping from the same period when it began the commercial production of oil).

The same trend has been the case for Nigeria’s export to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Europe. Kanya Williams, Head of Oil and Gas Office at the CBN, in his contribution to the Nigerian Association of Energy Economics Newsletter notes that, ‘energy efficiency has led to gradual reduction of crude oil demand affecting the Nigeria’s Bonny Light in this zone’. This is due to the implementation of stringent policies to transition to low-carbon economies as part of mitigation efforts to check climate change.

Nigeria’s woes are further compounded because of the nation’s overdependence on crude oil generated revenue. Government revenue, according to calculations from the Central bank’s data, dipped by 31 % between October, 2015 and June, 2016. This was the period within which the Bonny Light commanded its lowest price of US$30.66 over the last decade.

However, there are hopes that the intervention of OPEC will help to readjust the imbalance between supply and demand in the market. By its next meeting in November, it will reach a decision to ration the production of oil to 33 million barrels per day, this may stabilise the Brent price between US$50-US$60 (cnbc.com). Even if this is achieved, how long can this last to adequately stabilise the market again?

There is no comfortable time soon. Intense shale prospecting is ongoing in some countries and this is bound to force supply up again, returning the market to its previous state of imbalance. The national government of the UK has indicated its desire to endorse the production of oil and gas from its shale reserves, which the British Geological Survey estimates to be above 1.33 trillion cubic feet, in Central England only (upstreamonline). Currently, shale reserve estimates in China, one of Nigeria’s crude oil market, stands at 1115 trillion cubic feet. Production is expected to rise because of advancement in technology and the rapid development of the economics of shale oil, which has made shale exploration more cost effective.

Apart from this, the adoption of the enhanced oil recovery (EOR) technique by some producers of conventional oil like the UK, is facilitating more oil flows from wells already nearing the end of their commercial life.

The take home from all of these is that Nigeria cannot afford to continue leaning on the oil sector for too long. Even if the government’s plan to of exploring oil in frontier basins yield meaningful results, it will only be exacerbating the supply-led instability in the market. Not even an envisaged rise in China’s energy demand nor any of the emerging economies will be potent enough to effect surplus output in the oil market.

Now is the time for the government to act out its various plans of diversifying the economy. The non-oil sector like agriculture, industry and services have suffered major setbacks due to their neglect in previous years.

Written by Francis Effiong, He can be followed on Twitter @frankeffiong1